What internet regulations and the “lying flat” phenomenon have in common

Recent developments in China have produced a plethora of new buzzwords and phrases

Over the past few months, research material and discussion topics related to China have primarily focused on the following developments and phenomena:

- Internet company regulations (drive by the government to regulate what is seen as unfair competition among internet companies)

- “Common prosperity” (initiative to narrow the wealth gap)

- “China is uninvestable” (a common lament that seems to emerge every few years)

- Variable interest entity (VIE) structure (businesses that used the structure to gain access to capital markets outside of China potentially facing government crackdowns)

- “Lying flat” (phenomenon among some young people to forego the social and economic rat race, opting instead to do the minimum to get by)

- “Three Mountains” (high costs in education, healthcare and housing seen to be discouraging young people from having children, potentially posing serious social issues for China as its population ages rapidly)

- “Regulatory reset” (China’s seemingly abrupt regulatory shift in areas such as cryptocurrencies, fintech, carbon emissions and its digital economy)

The terms above seem be random and have little in common. However, these buzzwords are interlinked by the fact that they are seen reflecting the Chinese government’s current thinking and priorities, in addition to investors’ present views of the country. The key for the Chinese government is to strike a balance between economic growth and societal cohesion as it appears to believe that a “growth at all costs” model is no longer viable for China at this stage of the country’s economic development. This may change the way investors view opportunities in China. However, the underlying dynamic is expected to remain unchanged, potentially providing lucrative outcomes for well-executed strategies.

Is China uninvestable yet again? Taking a look at history

What are perceived as the negative aspects of current developments in China, such as government regulatory crackdowns on internet companies, have received a great deal of attention, giving rise to the view that “China is uninvestable”. But such a lament has re-emerged every three to five years. Investor concerns over China surfaced with the debt driven “crisis” (which did not materialise) of 2011, the anti-corruption campaigns of 2014 and the beginning of the US-China trade war in 2018, still fresh in memory. However, investing in China during these phases led to substantial returns.

Amid the current negative press, there are three factors to keep in mind when viewing China. First, sectors and trends that lead the Chinese capital markets tend to change every five to eight years. It was the financial and material sectors that were leading the capital markets in 2008, before consumers assumed the lead role in the early 2010s. Over the past five years, internet companies have become the leaders of the capital markets. The emergence of a new leader in the capital markets generally generates significant returns for investors. Second, China enacts what they view as internal reforms and deals with domestic issues when the country is robust and the economically strong. Third, the negative press about China obfuscates many of the positive developments taking place in the country.

Understanding the motive behind China’s regulations

Did it all begin with Ant Group?

A common narrative is that China began its regulations campaign when Ant Group’s IPO, which was supposed to be the world’s largest, was called off by regulators in November 2020. The government launched a series of actions against the internet industry in the following months, affecting heavyweights such as Tencent, Baidu, BABA and Weibo. However, many of the laws and directives encompassing not only the internet sphere, but also data security and personal information, social insurance and VIE structure space had already been put in effect or had been undergoing consultations since 2018.

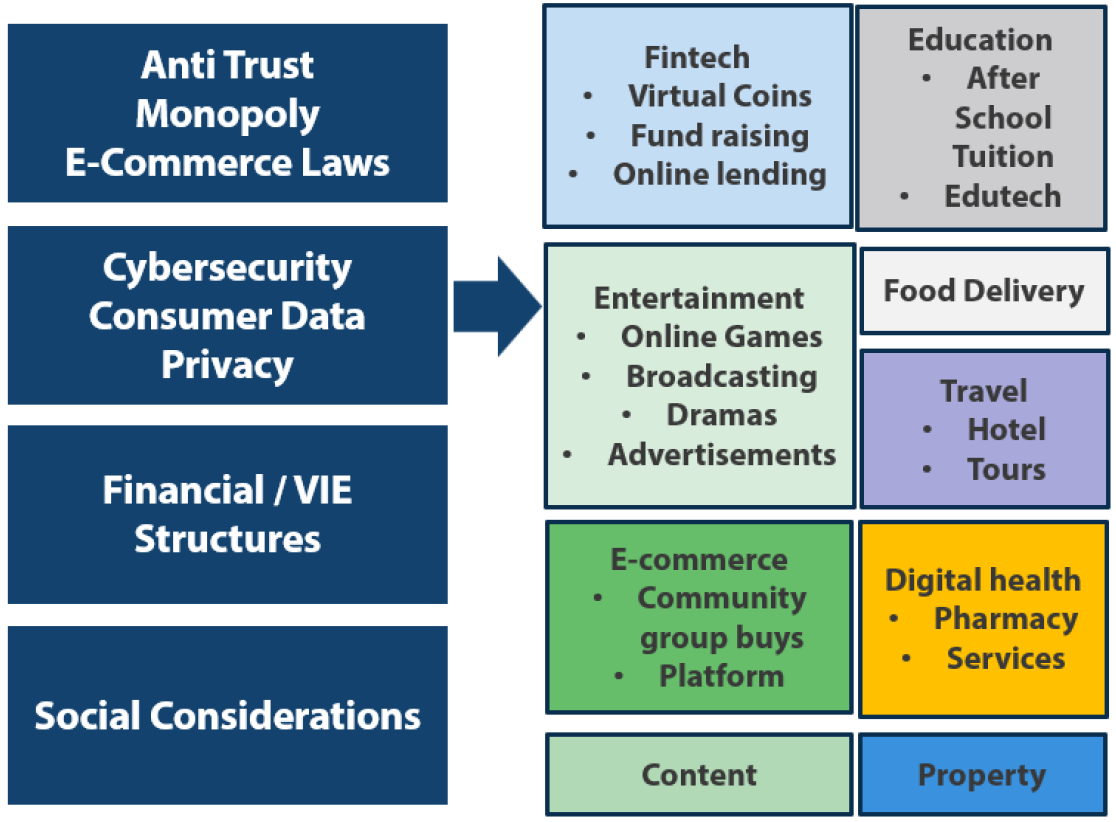

For example, the regulations impacting the internet industry are drawn from laws passed several years ago, reinforced by new laws to enhance enforcement and compliance. The laws impacted broad groups linked to internet companies, notably fintech, entertainment, e-commerce and content, and are wide ranging (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Series of laws continue to target specific areas in the internet industry

Source: Nikko AM

Source: Nikko AM

Factors driving the regulation initiative

China’s regulation initiative is being driven by an attempt to address threats to the economy and people’s livelihoods, to keep the country competitive against the US and to tackle social issues, in our view. One way China aims to address a threat to the economy and livelihoods through regulation is by narrowing the wealth gap. Economic disparity in China has widened to serious levels, which could potentially lead to other social issues and destabilise the economy. Regulation can also be utilised to tackle unfair practices and provide protection for workers, in addition to rectifying developments which have stifled innovation and the movement of capital by allowing a handful of companies to dominate an industry, such as has happened in China’s internet industry.

In China’s ongoing rivalry with the US, regulation could play a key role as Beijing tries to gain the upper hand in various fronts, moving focus away from the internet—which the government could now be viewing as an old, maturing technology—and directing capital to more strategic areas of innovation such as semiconductors, EVs, defense technology, drones, software and advanced manufacturing.

Regarding social considerations, tackling the country’s declining birth rate, which has continued to drop despite the abolishment of the one child policy, is likely the chief aim of the government. Addressing the “lying flat” phenomenon and the “Three Mountains” of high costs in education, healthcare and housing are seen as initiatives aimed at raising the birth rate.

Case studies: Is it wrong to regulate?

- Ant Group: In addition to having its IPO cancelled late in 2020, the fintech giant has also been accused of monopoly abuses and defying regulatory compliance requirements. A significant part of Ant Group’s revenue prior to the planned IPO originated from unsecured consumer online lending. Amid concerns that easy access to credit could eventually result in a subprime problem, the company is estimated to own about 15% of the country’s consumer loans. It has also been accused of unfair joint lending practices with banks, which have been forced to bear most of the lending risk.

- Didi Chuxing: The ride-hailing platform operator had its software pulled from app stores after it went public in the US in June. The authorities also launched a cybersecurity investigation aimed at preventing national security leaks stemming from an overseas listing. From a social issue perspective, the “take rate” that Didi takes from drivers (the amount of money Didi charges drivers for linking them with customers) raises the issue of fairness given the company’s monopolistic position. The data Didi holds could also be seen as too sensitive; according to media reports, the Cyberspace Administration of China said Didi improperly collected and used customer information.

- After-school tutoring (AST): Earlier in 2021 China clamped down on its booming tutoring industry, ordering private businesses to suspend after-school classes for children in a bid to lower expenditure by families. While AST may help improve grades, they are also known to expose students to severe amounts of stress. China is certainly not the first to curb AST: South Korea attempted to reign in its AST sector back in 2009 with mixed results. However, China’s impact on the capital markets was more pronounced and well-published due to its size, and due to the fact that many AST companies are listed in the US. Regulating AST has financial consequences for the industry, the size of which is estimated at around USD 100 billion, or about 0.7% of China’s GDP. But the social cost of keeping such a system intact could be too high. AST was also seen to be contributing to the formation of an elitist system, which may not bode well for a society aiming to narrow inequalities.

More to China than the internet

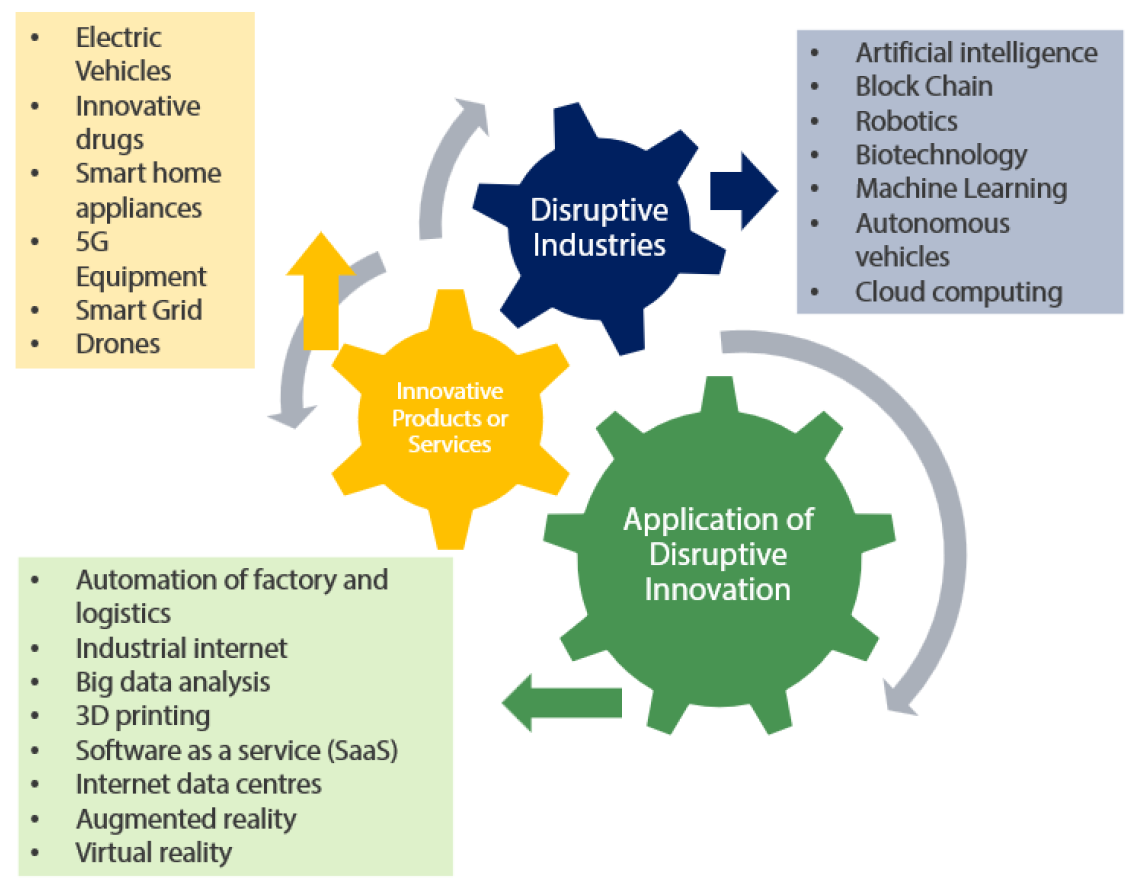

As China’s internet sector comes under scrutiny amid the government’s recent regulation initiative, we note that there is much more the country has to offer in the technology and innovation space (Chart 2). Many of these areas are considered strategic to China and thereby receive a great deal of support from the government.

Chart 2: Technology and innovation areas considered strategic to China

Source: Nikko AM

Source: Nikko AM

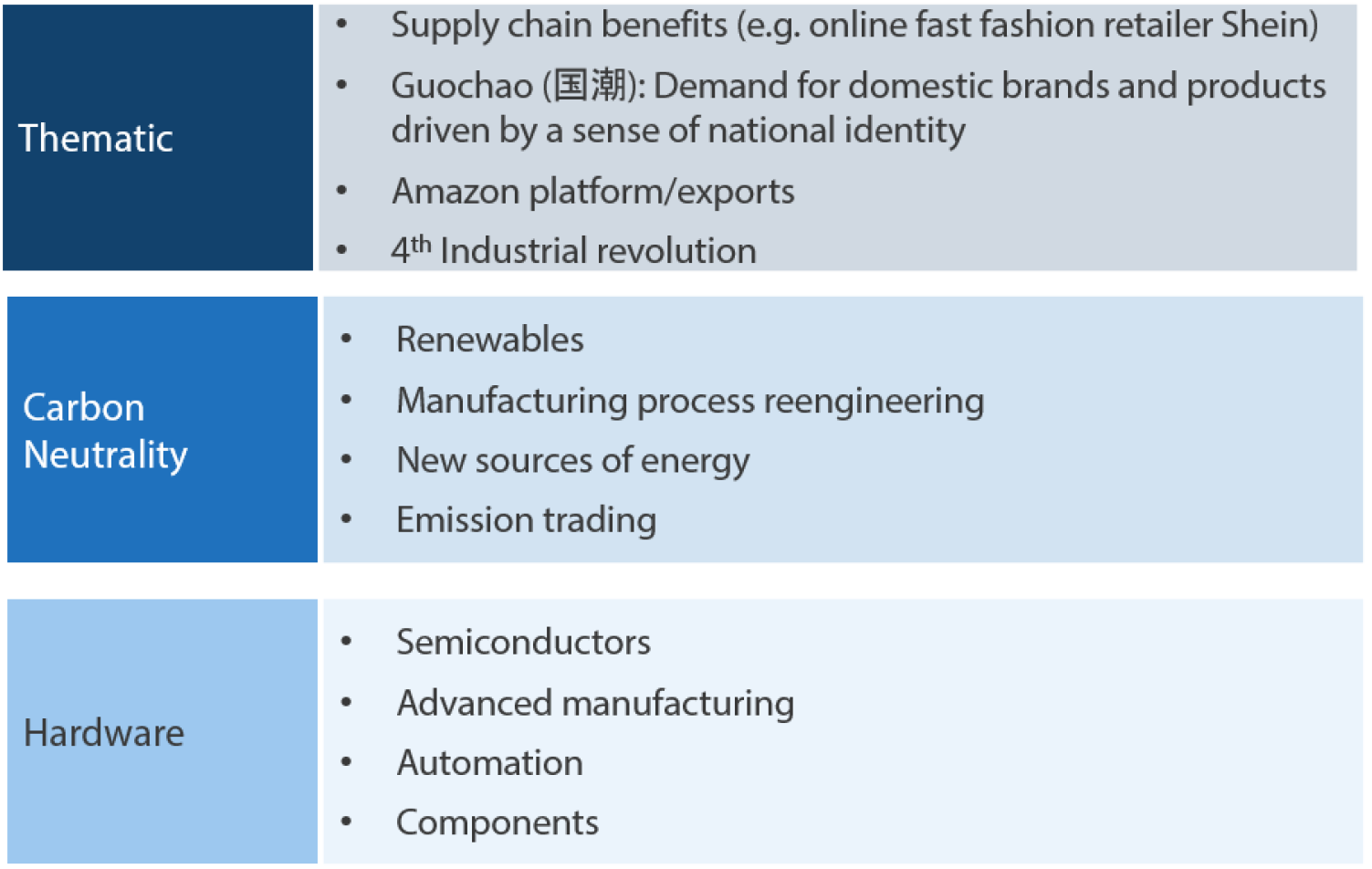

Even outside of disruptive technology and information, China has much to offer. We identify three main growth opportunity areas in China: those linked with thematic trends, decarbonization and hardware (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Key growth opportunity areas in China

Source: Nikko AM

Source: Nikko AM

The depth of the markets in China is second only to that of the US; it is also home to both dominant sectors not available elsewhere and emerging sectors that excite investors. Active investment, in our view, is a key factor in the very diverse Chinese capital markets in which the leaders change often.

Summary

We believe that China is proactively tackling excesses that could result in serious issues for society if left unaddressed. Many investors may have misread the Chinese government once again, underestimating the structural strength of the economy. Through the policies that are being enacted, we believe that (1) bad actors will be punished, (2) China will seek to strike a balance between economic growth and social cohesion and (3) China will continue to support areas it views at strategic to its economy. “Regulate to innovate” and/or “innovate, then regulate” are cycles within China; not every sector or company will emerge as winners from this cycle, so the key is being selective and identifying winners. Changes in government policies and regulations may help many sectors, creating new leaders in the capital markets in the process.